簡介

0.618,是黃金分割數的近似值,黃金分割數事實上是一個無理數。

相關

黃金分割數,(註:由於此為無限不循環小數,所以本文取近似值0.618)前面的2000位為:

0.6180339887 4989484820 4586834365 6381177203 0917980576

2862135448 6227052604 6281890244 9707207204 1893911374

8475408807 5386891752 1266338622 2353693179 3180060766

黃金分割

黃金分割 7263544333 8908659593 9582905638 3226613199 2829026788

0675208766 8925017116 9620703222 1043216269 5486262963

1361443814 9758701220 3408058879 5445474924 6185695364

8644492410 4432077134 4947049565 8467885098 7433944221

2544877066 4780915884 6074998871 2400765217 0575179788

3416625624 9407589069 7040002812 1042762177 1117778053

1531714101 1704666599 1466979873 1761356006 7087480710

1317952368 9427521948 4353056783 0022878569 9782977834

7845878228 9110976250 0302696156 1700250464 3382437764

8610283831 2683303724 2926752631 1653392473 1671112115

8818638513 3162038400 5222165791 2866752946 5490681131

7159934323 5973494985 0904094762 1322298101 7261070596

1164562990 9816290555 2085247903 5240602017 2799747175

3427775927 7862561943 2082750513 1218156285 5122248093

9471234145 1702237358 0577278616 0086883829 5230459264

7878017889 9219902707 7690389532 1968198615 1437803149

9741106926 0886742962 2675756052 3172777520 3536139362

1076738937 6455606060 5921658946 6759551900 4005559089

5022953094 2312482355 2122124154 4400647034 0565734797

6639723949 4994658457 8873039623 0903750339 9385621024

2369025138 6804145779 9569812244 5747178034 1731264532

2041639723 2134044449 4873023154 1767689375 2103068737

8803441700 9395440962 7955898678 7232095124 2689355730

9704509595 6844017555 1988192180 2064052905 5189349475

9260073485 2282101088 1946445442 2231889131 9294689622

0023014437 7026992300 7803085261 1807545192 8877050210

9684249362 7135925187 6077788466 5836150238 9134933331

2231053392 3213624319 2637289106 7050339928 2265263556

2090297986 4247275977 2565508615 4875435748 2647181414

5127000602 3890162077 7322449943 5308899909 5016803281

1219432048 1964387675 8633147985 7191139781 5397807476

1507722117 5082694586 3932045652 0989698555 6781410696

8372884058 7461033781 0544439094 3683583581 3811311689

9385557697 5484149144 5341509129 5407005019 4775486163

0754226417 2939468036 7319805861 8339183285 9913039607

2014455950 4497792120 7612478564 5916160837 0594987860

0697018940 9886400764 4361709334 1727091914 3365013715

令人驚訝的是,人體自身也和0.618密切相關,對人體解剖很有研究的義大利畫家達·文西發現,人的肚臍位於身長的0.618處;咽喉位於肚臍與頭頂長度的0.618處;肘關節位於肩關節與指頭長度的0.618處;鼻子位於頭頂與下巴長度的0.618處,人體存在著肚臍、咽喉、膝蓋、肘關節、鼻子五個黃金分割點,它們也是人賴以生存的五處要害。

黃金分割與人的關係相當密切。地球表面的緯度範圍是0——90°,對其進行黃金分割,則34.38°——55.62°正是地球的黃金地帶。無論從平均氣溫、年日照時數、年降水量、相對濕度等方面都是具備適於人類生活的最佳地區。說來也巧,這一地區幾乎囊括了世界上所有的已開發國家。

醫學與0.618有著千絲萬縷的聯繫,它可解釋人為什麼在環境22至24攝攝氏度時感覺最舒適。因為人的體溫為37°C與0.618的乘積為22.8°C,而且這一溫度中肌體的新陳代謝、生理節奏和生理功能均處於最佳狀態。科學家們還發現,當外界環境溫度為人體溫度的0.618倍時,人會感到最舒服.現代醫學研究還表明,0.618與養生之道息息相關,動與靜是一個0.618的比例關係,大致四分動六分靜,才是最佳的養生之道。醫學分析還發現,飯吃六七成飽的幾乎不生胃病。

高雅的藝術殿堂里,自然也留下了黃金數的足跡.畫家們發現,按0.618:1來設計腿長與身高的比例,畫出的人體身材最優美,而現今的女性,腰身以下的長度平均只占身高的0.58,因此古希臘維納斯女神塑像及太陽神阿波羅的形象都通過故意延長雙腿,使之與身高的比值為0.618,從而創造藝術美.難怪許多姑娘都願意穿上高跟鞋,而芭蕾舞演員則在翩翩起舞時,不時地踮起腳尖.音樂家發現,二胡演奏中,“千金”分弦的比符合0.618∶1時,奏出來的音調最和諧、最悅耳。

太陽系所在的位置,正好也是銀河系半徑的黃金分割帶上。

把一條線段分割為兩部分,使其中一部分與全長之比等於另一部分與這部分之比。其比值是一個無理數,取其前三位數字的近似值是0.618。由於按此比例設計的造型十分美麗,因此稱為黃金分割,也稱為中外比。這是一個十分有趣的數字,我們以0.618來近似,通過簡單的計算就可以發現:

1/0.618=1.618

(1-0.618)/0.618=0.618

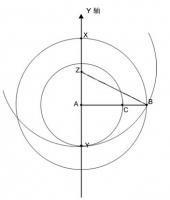

AE:BE=0.618 圖示

AE:BE=0.618 圖示 這個數值的作用不僅僅體現在諸如繪畫、雕塑、音樂、建築等藝術領域,而且在管理、工程設計等方面也有著不可忽視的作用。

0.618是短的比長的,而1.618是他的倒數.

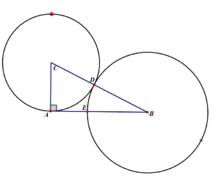

你可以在一個三角形上畫出黃金分割.

AB=2AC

∠A=90度

以C為圓心AC為半徑交BC於D

再以B為圓心BD為半徑交AB於E

AE:BE=0.618

還有:

(√5-1)/2=0.618

(√5+1)/2=1.618

發現歷史

古希臘帕提儂神廟是舉世聞名的完美建築,它的高和寬的比是0.618。建築師們發現,按這樣的比例來設計殿堂,殿堂更加雄偉、美麗;去設計別墅,別墅將更加舒適、漂亮.連一扇門窗若設計為黃金矩形都會顯得更加協調和令人賞心悅目。

由於公元前6世紀古希臘的畢達哥拉斯學派研究過正五邊形和正十邊形的作圖,因此現代數學家們推斷當時畢達哥拉斯學派已經觸及甚至掌握了黃金分割。

公元前4世紀,古希臘數學家歐多克索斯第一個系統研究了這一問題,並建立起比例理論。他認為所謂黃金分割,指的是把長為L的線段分為兩部分,使其中一部分對於全部之比,等於另一部分對於該部分之比。而計算黃金分割最簡單的方法,是計算斐波那契數列1,1,2,3,5,8,13,21,...後二數之比2/3,3/5,5/8,8/13,13/21,...近似值的。

黃金分割在文藝復興前後,經過阿拉伯人傳入歐洲,受到了歐洲人的歡迎,他們稱之為"金法",17世紀歐洲的一位數學家,甚至稱它為"各種算法中最可寶貴的算法"。這種算法在印度稱之為"三率法"或"三數法則",也就是我們現在常說的比例方法。

公元前300年前後歐幾里得撰寫《幾何原本》時吸收了歐多克索斯的研究成果,進一步系統論述了黃金分割,成為最早的有關黃金分割的論著。

中世紀後,黃金分割被披上神秘的外衣,義大利數家帕喬利稱中末比為神聖比例,並專門為此著書立說。德國天文學家克卜勒稱黃金分割為神聖分割。

其實有關"黃金分割",我國也有記載。雖然沒有古希臘的早,但它是我國古代數學家獨立創造的,後來傳入了印度。經考證。歐洲的比例算法是源於我國而經過印度由阿拉伯傳入歐洲的,而不是直接從古希臘傳入的。

到19世紀黃金分割這一名稱才逐漸通行。黃金分割數有許多有趣的性質,人類對它的實際套用也很廣泛。最著名的例子是優選學中的黃金分割法或0.618法,是由美國數學家基弗於1953年首先提出的,70年代由華羅庚提倡在中國推廣。

人與黃金分割

在人體中包含著多種“黃金分割”的比例因素,至少可以找出18個“黃金點”(如:臍為頭頂至腳底之分割點、喉結為頭頂至臍分割點、眉間點為發緣點至頦下的分割點等)幾乎身體相鄰的每一部分都成黃金比,隨著人類對自然界(動物、植物、宇宙、人類自身)的認識的日益深入,人類關於“黃金分割比”這一神奇比例的了解也越來越豐富:人體最適應的溫度乃是用黃金分割率切割自身的溫度,因為人正常體溫是37.5度,它和0.618的乘積為23.175℃,在這一環境溫度中,機體的新陳代謝、生理節奏和生理功能均處於最佳狀態。

人們發現自然界中這一神奇比例幾乎無所不在。從低等的動植物到高等的人類,從數學到天文現象中,幾乎都暗含著這種比例結構。

植物與黃金分割

人們發現,植物葉子,千姿百態,生機盎然,給大自然帶來了美麗的綠色世界.儘管葉子形態隨種而異,但它在莖上的排列順序(稱為葉序),是極有規律的,不是雜亂無章的。你從植物莖的頂端向下看,經細心觀察,發現上下層中相鄰的兩片葉子之間約成137.5°角.如果每層葉子只畫一片來代表,第一層和第二層的相鄰兩葉之間的角度差約是137.5°,以後二到三層,三到四層,四到五層……兩葉之間都成這個角度.植物學家經過計算表明:這個角度對葉子的採光、通風都是最佳的.葉子的排布,多么精巧!

葉子間的137.5°角中,藏有什麼“密碼”呢?我們知道,一周是360°,

360°-137.5°=222.5°

137.5°∶222.5°≈0.618.

瞧,這就是“密碼”!葉子的精巧而神奇的排布中,竟然隱藏著0.618,準確符合數學中的“黃金分割律”。

梨樹也是如此,它的葉片排列是沿對數螺鏇上升,這也保證了葉與葉之間不會重合,下面的葉片正好在從上面葉片間漏下陽光的空隙地方,這是採光面積最大的排列方式。可見,沿對數螺鏇按圓的黃金分割盤鏇而生,是葉片排列的最優良選擇。

同樣在一片葉子中也有黃金分割的現象存在。主葉脈與葉柄和主葉脈的長度之和比約為0.618;向日葵花盤和松果的螺線、植物莖幹上的幼芽分布、種子發育成形 和動物犄角的生長定式,遵循著黃金分割率。

建築與黃金分割

金字塔的幾何形狀有五個面,八個邊,總數為十三個層面。由任何一邊看入去,都可以看到三個層面。金字塔的長度為5813寸(5-8-13)。無論是古希臘帕特農神廟,還是中國古代的兵馬俑,它們的垂直線與水平線之間竟然完全符合1比0.618的比例。法國巴黎聖母院的正面高度和寬度的比例是8:5,它的每一扇窗戶長寬比例也是如此。 黃浦江東岸的 東方明珠廣播電視塔,塔身高達468米。紐約聯合國大樓在建築設計中所運用的黃金分割率。

宇宙與黃金分割

我們知道,太陽系內目前共發現有八大行星。然而早在18世紀中葉,德國的自然科學家提丟斯就發現,如將0、3、6、12、24、48、96數列中的每個數加4,而得數用10來除,其結果是:

(0+4)÷10=0.4 (水星距離太陽實際0.387天文單位)

(3+4)÷10=0.7 (金星距離太陽實際0.723天文單位)

(6+4)÷10=1.0 (地球距離太陽實際1.000天文單位)

(12+4)÷10=1.6 (火星距離太陽實際1.524天文單位)

(24+4)÷10=2.8 (小行星帶)

(48+4)÷10=5.2 (木星距離太陽實際5.203天文單位)

(96+4)÷10=10 (土星距離太陽實際9.56天文單位)

通過以上數字對比我們可以看出,提丟斯計算出的數值與各行星至太陽的實際距離確實是十分相近的。1766年,提丟斯在把《自然的探索》這本書從法文翻譯成德文的時候,也順便將他發現的這一規律加進書中。但此書出版後並沒有引起人們的普遍關注。1772年,柏林天文台台長波得注意到了這-奇特的規律,並將它編寫到《星空研究指南》一書中進行介紹,這就是後人經常提到的提丟斯—-波得定則。但需要說明的是:為什麼是0、3、6、12、24、48這樣的數列加4再用10來除而不是別的什麼數?提丟斯和波得都沒有做出任何解釋。裡面包含著什麼奧秘?他們倆也都沒有說明。

近年來,有人用黃金分割法來計算各行星至太陽的距離,其結果同樣令人驚訝!

0.732×0.618=0.446(水星距太陽實際0.387天文單位)

1.000×0.618=0.618(金星距太陽實際0.723天文單位)

1.52×0.618=0.939(地球距太陽實際1.000天文單位)

2.80×0.618=1.73 (火星距離太陽實際1.52天文單位)

5.20×0.618=3.213(小行星帶距太陽實際2.8天文單位)

9.54×0.618=5.89 (木星距太陽實際5.2天文單位)

19.2×0.618=11.86 (土星距太陽實際9.54天文單位)

30.1×0.618=18.601(天王星距太陽實際19.2天文單位)

:1個天文單位等於1.5億千米

從以上數字我們可以看出,除土星至太陽的實際距離誤差稍大些外,其它行星至太陽的距離數值都還是很接近的。如果我們再考慮到各行星之間的相互引力及偏心率問題,計算數值會顯得更要精確一些。如土星除受太陽的吸引力外,還要受木星巨大引力的影響,故它的實際距離小於計算值就不難理解了。當然,用黃金分割法計算各行星至太陽間的距離,同提丟斯—-波得定則一樣,在海王星和冥王星的計算上受到了挑戰,其原因還有待於繼續分析研究。

我們知道,銀河系是一個巨大的天體系統,其中恆星占了90%,氣體和塵埃占了10%,而這些物質大部分匯聚在中央平面的附近繞銀河中心運行。從側面來看我們的銀河系,它就像一個扁扁的鐵餅,整個直徑有25千秒差距至30千秒差距,而我們人類居住的地球和太陽系,就處在距銀河系中心8.5千秒差距的地方。近年來又有人發現:我們的太陽系所在的位置,正好也是銀河系半徑的黃金分割帶上。即:27.5÷2×0.618=8.4975(千秒差距)

黃金分割

黃金分割 奇妙的“黃金數”

取一條線段,線上段上找到一個點,使這個點將線段分成一長一短兩部分,而長段與短段的比恰好等於整段與長段的比,這個點就是這條線段的黃金分割點。這個比值為:1:0.618…而0.618…這個數就被叫作“黃金數”。

有趣的事,這個數在生活中隨處可見:人的肚臍是人體總長的黃金分割點;有些植物莖上相鄰的兩片葉子的夾角恰好是把圓周分成1:0.618…的兩條半徑的夾角。據研究發現,這種角度對植物通風和採光效果最佳。

建築師們對數0.618…特別偏愛,無論是古埃及的金字塔,還是巴黎聖母院,或是近代的艾菲爾鐵塔,都少不了0.618…這個數。人們還發現,一些名畫,雕塑,攝影的主體大都在畫面的0.618…處。音樂家們則認為將琴馬放在琴弦的0.618…處會使琴聲更柔和甜美。

數0.618…還使優選法成為可能。優選法是一種求最最佳化問題的方法。如在煉鋼時需要加入某種化學元素來增加鋼材的強度,假設已知在每噸鋼中需加某化學元素的量在1000—2000克之間。為了求得最恰當的加入量,通常是取區間的中點進行試驗,然後將實驗結果分別與1000克與2000克時的實驗結果作比較,從中選取強度較高的兩點作為新的區間,再取新區間的中點做實驗,直到得到最理想的效果為止。但這種方法效率不高,如果將試驗點取在區間的0.618處,效率將大大提高,這種方法被稱作“0.618法”,實踐證明,對於一個因素的問題,用“0.618法”做16次試驗,就可以達到前一種方法做2500次試驗的效果!

“黃金數”在生活中竟有如此多的實例和運用。或許,在它的身上,還有更多的奧秘,等待我們去探尋,使它能更好地為我們服務,為我們解決更多問題。

軍事與黃金分割

0.618,一個極為迷人而神秘的數字,而且它還有著一個很動聽的名字——黃金分割律,它是古希臘著名哲學家、數學家畢達哥拉斯於2500多年前發現的。古往今來,這個數字一直被後人奉為科學和美學的金科玉律。在藝術史上,幾乎所有的傑出作品都不謀而合地驗證了這一著名的黃金分割律,無論是古希臘帕特農神廟,還是中國古代的兵馬俑,它們的垂直線與水平線之間竟然完全符合1比0.618的比例。

0.618與武器裝備

在冷兵器時代,雖然人們還根本不知道黃金分割率這個概念,但人們在製造寶劍、大刀、長矛等武器時,黃金分割率的法則也早已處處體現了出來,因為按這樣的比例製造出來的兵器,用起來會更加得心應手。

當發射子彈的步槍剛剛製造出來的時候,它的槍把和槍身的長度比例很不科學合理,很不方便於抓握和瞄準。到了1918年,一個名叫阿爾文·約克的美遠征軍下士,對這種步槍進行了改造,改進後的槍型槍身和槍把的比例恰恰符合0.618的比例。

實際上,從鋒利的馬刀刃口的弧度,到子彈、炮彈、彈道飛彈沿彈道飛行的頂點;從飛機進入俯衝轟炸狀態的最佳投彈高度和角度,到坦克外殼設計時的最佳避彈坡度,我們也都能很容易地發現黃金分割率無處不在。

在大炮射擊中,如果某種間瞄火炮的最大射程為12公里,最小射程為4公里,則其最佳射擊距離在9公里左右,為最大射程的2/3,與0.618十分接近。在進行戰鬥部署時,如果是進攻戰鬥,大炮陣地的配置位置一般距離己方前沿為1/3倍最大射程處,如果是防禦戰鬥,則大炮陣地應配置距己方前沿2/3倍最大射程處。

0.618與戰術布陣

在我國歷史上很早發生的一些戰爭中,就無不遵循著0.618的規律。春秋戰國時期,晉厲公率軍伐鄭,與援鄭之楚軍決戰於鄢陵。厲公聽從楚叛臣苗賁皇的建議,把楚之右軍作為主攻點,因此以中軍之一部進攻楚軍之左軍;以另一部進攻楚軍之中軍,集上軍、下軍、新軍及公族之卒,攻擊楚之右軍。其主要攻擊點的選擇,恰在黃金分割點上。

把黃金分割律在戰爭中體現得最為出色的軍事行動,還應首推成吉思汗所指揮的一系列戰事。數百年來,人們對成吉思汗的蒙古騎兵,為什麼能像颶風掃落葉般地席捲歐亞大陸頗感費解,因為僅用遊牧民族的彪悍勇猛、殘忍詭譎、善於騎射以及騎兵的機動性這些理由,都還不足以對此做出令人完全信服的解釋。或許還有別的更為重要的原因?仔細研究之下,果然又從中發現了黃金分割律的偉大作用。蒙古騎兵的戰鬥隊形與西方傳統的方陣大不相同,在它的5排制陣形中,人盔馬甲的重騎兵和快捷靈動輕騎兵的比例為2:3,這又是一個黃金分割!你不能不佩服那位馬背軍事家的天才妙悟,被這樣的天才統帥統領的大軍,不縱橫四海、所向披靡,那才怪呢。

馬其頓與波斯的阿貝拉之戰,是歐洲人將0.618用於戰爭中的一個比較成功的範例。在這次戰役中,馬其頓的亞歷山大大帝把他的軍隊的攻擊點,選在了波斯大流士國王的軍隊的左翼和中央結合部。巧的是,這個部位正好也是整個戰線的“黃金點”,所以儘管波斯大軍多於亞歷山大的兵馬數十倍,但憑藉自己的戰略智慧,亞歷山大把波斯大軍打得潰不成軍。這一戰爭的深刻影響直到今天仍清晰可見, 在海灣戰爭中,多國部隊就是採用了類似的布陣法打敗了伊拉克軍隊。

兩支部隊交戰,如果其中之一的兵力、兵器損失了1/3以上,就難以再同對方交戰下去。正因為如此,在現代高技術戰爭中,有高技術武器裝備的軍事大國都採取長時間空中打擊的辦法,先徹底摧毀對方1/3以上的兵力、武器,爾後再展開地面進攻。讓我們以海灣戰爭為例。戰前,據軍事專家估計,如果共和國衛隊的裝備和人員,經空中轟炸損失達到或超過50%,就將基本喪失戰鬥力。為了使伊軍的損耗達到這個臨界點,美英聯軍一再延長轟炸時間,持續38天,直到摧毀了伊拉克在戰區內428輛坦克中的78%、2280輛裝甲車中的36%、3100門火炮中的91%,這時伊軍實力下降至60%左右,這正是軍隊喪失戰鬥力的臨界點。也就是將伊拉克軍事力量削弱到黃金分割點上後,美英聯軍才抽出“沙漠軍刀”砍向薩達姆,在地面作戰只用了100個小時就達到了戰爭目的。在這場被譽為“沙漠風暴”的戰爭中,創造了一場大戰僅陣亡百餘人奇蹟的施瓦茨科普夫將軍,算不上是大師級人物,但他的運氣卻幾乎和所有的軍事藝術大師一樣好。其實真正重要的並不是運氣,而是這位率領一支現代大軍的統帥,在進行戰爭的運籌帷幄中,有意無意地涉及了0.618,也就是說,他多多少少託了黃金分割律的福。

此外,在現代戰爭中,許多國家的軍隊在實施具體的進攻任務時,往往是分梯隊進行的,第一梯隊的兵力約占總兵力的2/3,第二梯隊約占1/3。在第一梯隊中,主攻方向所投入的兵力通常為第一梯隊總兵力的2/3,助攻方向則為1/3。防禦戰鬥中,第一道防線的兵力通常為總數的2/3,第二道防線的兵力兵器通常為總數的1/3。

0.618與戰略戰役

0.618不僅在武器和一時一地的戰場布陣上體現出來,而且在區域廣闊、時間跨度長的巨觀的戰爭中,也無不得到充分地展現。

一代梟雄的的拿破崙大帝可能怎么也不會想到,他的命運會與0.618緊緊地聯繫在一起。1812年6月,正是莫斯科一年中氣候最為涼爽宜人的夏季,在未能消滅俄軍有生力量的博羅金諾戰役後,拿破崙於此時率領著他的大軍進入了莫斯科。這時的他可是躊躇滿志、不可一世。他並未意識到,天才和運氣此時也正從他身上一點點地消失,他一生事業的頂峰和轉折點正在同時到來。後來,法軍便在大雪紛揚、寒風呼嘯中灰溜溜地撤離了莫斯科。三個月的勝利進軍加上兩個月的盛極而衰,從時間軸上看,法蘭西皇帝透過熊熊烈焰俯瞰莫斯科城時,腳下正好就踩著黃金分割線。

1941年6月22日,納粹德國啟動了針對蘇聯的“巴巴羅薩”計畫,實行閃電戰,在極短的時間裡,就迅速占領了的蘇聯廣袤的領土,並繼續向該國的縱深推進。在長達兩年多的時間裡,德軍一直保持著進攻的勢頭,直到1943年8月,“巴巴羅薩”行動結束,德軍從此轉入守勢,再也沒能力對蘇軍發起一次可以稱之為戰役行動的進攻。被所有戰爭史學家公認為蘇聯衛國戰爭轉折點的史達林格勒戰役,就發生在戰爭爆發後的第17個月,正是德軍由盛而衰的26個月時間軸線的黃金分割點。

黃金比率在人的世界(無論是生物環境還是社會環境)中幾乎是無所不在的。最有意味的是,在人的生命程式DNA分子中,也包含著“黃金分割比”。它的每個雙螺鏇結構中都是由長34個埃與寬21個埃之比組成的,當然34和21是斐波那契系列中的數字,它們的比率為1.6190476,非常接近黃金分割的1.6180339。這是否說明黃金分割律是比DNA中的遺傳密碼更基本的東西?因為承載DNA的結構——雙螺鏇結構——也遵循黃金分割律。黃金分割律也許是我們的宇宙的DNA中的遺傳密碼?

關於0.618的數學論文

做饅頭,鹼放少了饅頭會酸,鹼放多了饅頭會變黃、變綠且帶鹼味。鹼放多少才合適呢?這是一個優選問題;為了加強鋼的強度,要在鋼中加入碳,加入太多太少都不好。究竟加入多少碳,鋼才能達到最高強度呢?這也是一個優選問題。在日常生活和生產中,我們常常會遇到優選問題。

可是,鹼的多少與饅頭好壞之間的關係,碳的多少與鋼的強度之間的關係,如果不能簡單地用數學式子表示出來,那么,應該如何解決呢?我們不妨觀察一下炊事員學做饅頭的過程:這次鹼放多了,下次就放少一點,下次鹼放少了,再下次再放多一點,以此類推。試驗效果一次比一次好,最終獲得鹼的合適加入量,做出好饅頭。太妙了!炊事員給了我們啟示:用試驗的辦法來解決!

解答一個優選問題,往往需做若干次試驗。安排這些試驗的方法,必須選擇,講究科學。例如,對鋼中加入多少碳的優選問題,假設已估出每噸加入量在1000克到2000克之間。若用均分法來安排試驗,則應選取1001克、1002克...為試驗點,共需做一千次試驗。若按一天做一次試驗計算,則需花將近三年的時間才能完成。太費時了!在時間就是生命的今天,這種安排方法顯然不可取。有更科學的安排方法嗎?能否減少試驗次數,迅速找到最佳點呢?

為此,數學家們設計了運用數學原理科學地安排試驗的方法,這就是人們所說的“優選法”。數學大師華羅庚(1910──1985年)從1964年起,走遍大江南北的二十幾個省(市),推廣優選法。他在單因素優選問題中,用得最多的是0.618法。

0.618法是根據黃金分割原理設計的,所以又稱之為黃金分割法。

現在,我們用0.618法來安排上述的優選碳的加入量的試驗。

0.618法確定第一個試驗點是在試驗範圍的0.618處。這點的加入量可由下面公式算出:

(大-小)×0.618+小=第一點。①

第一點加入量為:

(2000-1000)×0.618+1000=1618(克)。

再在第一點的對稱點處做第二次試驗,這一點的加入量可用下面公式計算(此後各次試驗點的加入量也按下面公式計算):

大-中+小=第二點。②

第二點的加入量為:

2000-1618+1000=1382(克)。

比較兩次試驗結果,如果第二點比第一點好,則去掉1618克以上的部分;如果第一點較好,則去掉1382克以下部分。假定試驗結果第二點較好,那么去掉1618克以上的部分,在留下部分找出第二點的對稱點做第三次試驗。

第三點的加入量為:

1618-1382+1000=1236(克)。

再將第三次試驗結果與第二點比較,如果仍然是第二點好些,則去掉1236克以下部分,如果第三點好些,則去掉1382克以上部分,在留下部分找出第二點的對稱點做第四次試驗。

第四點加入量為:

1618-1382+1236=1472(克)。

第四次試驗後,再與第二點比較,並取捨。在留下部分用同樣方法繼續試驗,直至找到最佳點為止。

一次又一次試驗,一次又一次比較與取捨。從第二次試驗起,每次能去掉相應試驗範圍的382/1000,試驗範圍逐步縮小,最佳點逐步接近。因此,用0.618法能以較少的試驗次數,迅速找到最佳點。

不少工廠在配比配方、工藝操作條件等方面,用0.618法解決了優選問題,從而提高了質量,增加了產量,降低了消耗,取得了很好的經濟效益。例如,糧食加工通過優選加工工藝,一般可以提高出米率1~3%。如果按全國人口全年的口糧加工總數計算,一年就等於增產幾億千克糧食。你不妨找一個生活或生產中的優選問題,用0.618法去試一試,看能解決嗎?相信你能享受到成功的喜悅!

0.618的英文詮釋

The Golden Mean is a ratio which has fascinated generation after generation, and culture after culture. It can be expressed succinctly in the ratio of the number "1" to the irrational "l.618034... ", but it has meant so many things to so many people, that a basic investigation of what might is the "Golden Mean Phenomenon" seems in order. So much has been written over the centuries on the Mean, both fanciful imaginings and recondite mathematicizations, that a review of the literature on the subject would be oversize, and probably lose the focus of the problem.

This purpose of this paper is to state in the simplest form problems which relate to the Golden Mean, and pursue a variety of directions which aim to explain the origin of this remarkable ratio and its ultimate meaning in the world of mind and matter.

In modern times there has been much interest in the Golden Proportion, Section or Mean. Since the Renaissance it has been used extensively in art and architecture, it figures in the Venetian Church of St. Mark built early in the 16th century, and has become a standard proportion for width in relation to height as used in facades of buildings, in window sizing, in first story to second story proportion, at times in the dimensions of paintings and picture frames. There is something "satisfactory" about the relationships of the Greek "divided lines" proportion, which some have felt to be modern acculturation since the Renaissance. In the l930's the Pratt Institute of New York did a study on various rectangular proportions laid out as vertical frames, and asked several hundred art students to comment on which seemed the most pleasing. The ratio of 1 : 2 was least liked, while the Golden Ratio was favored by a very large margin, which seemed to point to the actual dimensions as generating a pleasing response by their size.

The French architect LeCorbusier noted that the human body when measured from foot to navel and then again from navel to top of head, showed average numbers very near to the Golden Ratio. He extended this to height compared with arm-span, and designed doorways consonant with these numbers. But of course much of this was based in averages rather than exact numbers, and so falls into the general area of esthetic design, rather than mathematical proportion.

However studies have shown that the patterns of tree- branching adhere to the GM proportion, although again not exactly, while the dendritic cracking in certain metallic alloys which occurs as very low temperatures is basically GM based. In an entirely different area, Duckworth at Princeton found in the early l940's a GM relationship in the length of paragraphs in Vergil's Aeneid, with the figures becoming ever more accurate as larger samples were taken. Lendvai has demonstrated that Bartok used the GM ratio extensively in composing music, the question remaining whether an artist as an educated person uses the GM ratio consciously as a framework for his work, or unconsciously because of its ubiquitous appearance in the world around us, something we sense by living in a GM proportioned world.

The Algebraic Approach

FIRST let us examine the Golden Section from a algebraic direction :

The Golden Section is the division of a given unit of length into two parts such that the ratio of the shorter to the longer equals the ratio of the longer part to the whole. Calling the longer part x and accordingly the shorter part 1-x, this condition reads

1-x is to x as x is to 1

(1-x)/x = x/1

This is solved by multiplying both sides by x, to get

1-x = x^2

or

x^2 + x - 1 = 0

The Quadratic Formula (x = (-b +/- sq.r.(b^2 - 4ac))/2a) applies here with a=1, b=1, c=-1, and yields the answer

x = (-1 + sqr(5))/2 =. 618, nearly.

2) SECOND I point to the circular method given in standard algebra textbooks, which I can not reproduce here since it demands a diagram and I am using a text-only format for this material. It follows Euclidean procedure in working with a circular display. Briefly, as far back as about 500 BC it was observed that in the regular decagon (figure of 10 equal sides inscribed in a circle), the triangle formed by one of the exterior segments and two radii will show the Golden Proportion in the ratio of short to long leg of that isosceles triangle. Incidentally, its base angles (72 degr.) are just twice its apex angle (36deg). A traditional description of this process in formal terms can be seen in E P Vance's Modern Algebra and Trigonometry, l962. or in any algebra textbook.

This is especially interesting in that it involves the construction of a pentagon and the 10 fold division of a circle, with dimensions which evolve from the 1 : 2 rectangle. The common denominator to both procedures is of course the sqr 5!

Perhaps it is better to see all this in diagram and follow the derivation as given there. This, compared with the previous section, is a somewhat different, non-quadratic way of finding the GM ratio, it is geometric and more in the spirit of the early Greek investigators than the algebraic methods given above.

An Approximative Approach

Here is a method of my own, proceeding by a series of approximations, which I present with enthusiasm, since I have seen no parallel to it elsewhere. Starting with the number one (1), I want to find any number larger than it, the inverse of which is smaller by the difference of one (1) while retaining the same digits. If I try random numbers, I find the difference either too large or too small, so by a rather exhausting session with the Method of Exhaustions, I find my numbers converging on the GM figures:

.618034 and 1 and 1.618034.

(In order to check accuracy I try it with 10/9 places::

1.6180339887 and. 618033989, with rounding off on my calculator, so we have a continuing series.)

By this crude and curious method I have avoided engaging , in true classical Greek fashion, with the irrational square root of 5, which the algebraic solutions brings up. I suspect that this method can only be done with numbers, that it has no analog with stick or string which a Greek architechtural workman could have used.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

A mathematical friend inspected this last method, and commented that I might point out to the general reader to the fact that the way. .618 is characterized in the exhaustions paragraph, stems from the first equation 1) above:

(1-x)/x = x

and write the left-hand side a 1/x - x/x, so you get

1/x - 1 = x

or 1/x = x + 1

This says that when you add 1 to the number you want (.618), you get the reciprocal of that number.

One way to home in on it, aside from the random approximations you mention, is as follows:

Start with any convenient number, e.g.. 5

Add 1 --- getting 1.5 in this case.

Form the reciprocal --- getting 1/1.5 or 0.667........

Add 1 --- getting 1.6

Form the reciprocal --- getting .625

Add 1

Form reciprocal..."

Soon you see convergence. You can start with any other number (between 0 and 1) in the place of. 5, and get the same. .618 ultimately.

Irrationals and the Greeks

Now we come to another approach, which I believe was the one the Greeks used. First let me set the stage with some background material which bears on my solution:

a) Plato had described in the Meno common knowledge about the squaring of the square, by constructing a larger square based on the hypotenuse of the original diagrammed square. He doubled the area, and neatly avoided having to deal with the square root of 2 by simply squaring it and returning it the realm of usable numbers. What he had been dealing with was of course 1.414213562....

b) With such interesting returns from the experiment with the square, a next natural trial might well be dealing with a rectangle with an adjacent side twice the length of its partner, hence a 1 : 2 rectangle. Now by Pythagorean theorem the hypotenuse will be the square root of 5 which the Greek cannot deal with, nor will it give an interesting return if handled like the 1 : 1 square. (A larger square based on this diagonal will have an area of 25, not consonant with the original rectangular area of 2, hence not interesting to a Greek. Dead-end in this direction.)

c) There is a note in Herodotus, speaking of the Egyptians and Egyptian mathematical knowledge.. H W Turnbull, the distinguished algebraist of the l940's, remarks in an essay in The Great Mathematicians, on Herodotus' passage:

"A certain obscure passage in Herodotus can, by the slightest literal emendation, be made to yield excellent sense. It would imply that the area of each triangular face of the Pyramid is equal to the square of the vertical height. and this accords well with the actual facts. If this be so, the ratios of height, slope and base can be expressed in terms of the Golden Section, of the radius of a circle to the side of the inscribed decagon. In short there was already a wealth of geometrical and arithmetical results treasured by the priests of Egypt, before the early Greek travelers became acquainted with mathematics..."

d) Herodotus also mentions that the Egyptians had a regular class of mathematical technicians, whom he calls "rope measurers", who were used not only to measure out linear distances for surveying, but to establish complex geometric figures. The convenient whole numbers associated with the Pythagorean theorem, 3, 4 and 5 and any multiples of these, were well known to the Egyptians as basic information. Considering the complexities involved in the dimensioning of the Pyramids, it is clear that the rope measurers were the standard way of converting mathematical data to actual, architectural measurements. I mention this as especially important in relation to the following: section:

Measurements and the Parthenon

It has always been a problem to undertand how the Greek architect and his consruction workers managed to incorporate into the design of large-scale temples like the Parthenon the "irrational" measurements which the Golden Mean requires. The Greeks had no system for handling irrational numbers in a theoretical manner, let alone applying irrational measurements to an actual conctruction project. Extending the numbers of the GM proportion from one place to another on a building in the process of construction would seem to have been impossible.

But the proportions are clearly there in fact. So at this point I want to introduce a method, which I take to be an independent discovery on my part, and the key to the use of the GM ratio in large scale applications in architecture, for example in Iktinos' GM based designs for the Parthenon..

a) I construct a 1 : 2 rectangle of any size, depending on what scale I am working with.

b) I fix a non-elastic string or tape to the lower left hand corner of this rectangle, and run it around a point (a nail) at the upper right hand corner then draw it down to the lower right corner. This adds the short side of the rectangle (1) to the diagonal (sqrt5).

c) I then take my string, hold the ends together, and stretching it out double, I halve its length. This is now (sqrt 5+1)/2 or numerically 1.618....., the number have been seeking for comparison to one (1).

d) I can take this string/number and use it as short side of a new larger rectangle, and construct a new larger rectangular figure with the same proportions preserved.

e) But I may want to get smaller, that is find the inverse (1/x) of 1.618 (which is. 618), I can do this by the string method too. I draw my line from left lower to right upper corner, bring down the line to lower right corner, and folding that back along the diagonal, I mark that point, which represents the subtraction of one (1) from sqrt5. If I take that remaining length of my line from the start to the mark, and fold it double, I get. 618 or the inverse of 1.618 (1/x).

To us in a day of exact measurements with electronic drafting equipment, it may seem inconvenient to make architectural measurements with a string, but recall that all measurements of objects in the real world are still made with linear devices. In the West we now use a plastic tape of high strength with low expansion, before that it was a woven marked tape laced with copper wires, earlier the "chain" and "rod" which were standards set to a given length. Surveyors still use tapes, usually of steel with a calculation for drop under a specific tension, rather than available optical distance measuring equipment, since they are more accurate for standard civil engineering work. The rolling pi-wheel is used on highways for initial measurement, but never replaces the tape. (It is only in recent years that we have adopted use of wave lengths from certain elements (cadmium) at a fixed temperature, as a standard of length, but that is in laboratory situations only for establishing standards.)

The Greeks as carpenters, masons and architects, used direct measurement, that is, measurements transferred from one block or board to another which was to be made identical as possible Their constant mention of "congruence" points to this simple matching of direct size, which "congrue" if they match up in all their dimensions. Although the Greek mathematical intellectuals had a tendency to mask their connections with the handicrafts and trades as functioning on a lower plane, architecture and manufacturing were everywhere present in their society. The problem in this case is bringing together the Greek mathematical knowledge of the geometers with the practical transfer of mathematical proportions to actual buildings.

In short, I believe the Greeks first explored the possibilities inherent in the rectangle of 1 : 2 ratio, and found that this satisfied in realizable dimensions the ideal proportion which Plato had discussed in his projection of the Divided Line.. The next step was devising a (string) method which would permit transfer of proportional measurements to real objects under construction.

Plato had said that a line so divided into two unequal segments so that the smaller bore the same relationship to the larger, and the larger to the whole line, would represent a special kind of proportional relationship with important properties. Euclid discussed this relationship in his book on proportional in geometric terms, naturally stopping short of identifying exact numbers, which would have been inconceivable with the primitive Greek numerical system. That this was a commonly understood and accepted ratio can be inferred from its extensive use in the work of the 5th century architect Iktinos, who designed the Parthenon with the Golden Mean ratio throughout..

A "Standard" for the Proportions

Let me describe an important area which should be investigated by someone who has an interest in the proportional measurements of the Parthenon. If we take several of the larger proportions which are well documented with fair agreement of the numbers, and if we scale these down to a size which should represent a working "Standard Scale", as the official basic measurement from which the rope calculators would start their numerical expansions, we would expect to find a "Parthenon-Standard" from which the enlarged proportions used in the construction of the Parthenon were developed.

It would not be surprising to find this standard in the range of a human cubit. Since the Greeks were smaller then that Western persons at the present time, I would expect this Standard to be somewhat under the nineteen inches common for a well developed American male. But if no figure in this range emerged, then we would look for another standard for the basic measurement, and it could be one drawn from some other human or animal figure, or it could be entirely arbitrary.

What is the value of this Standard? It would provide the link between a physical measurement, which could be a master-measurement on a strip of wood or metal, used in conjunction with the non-numerical calculations of the "Rope Measurers" whose work was entirely proportional. If the architectural measurements taken from a finished building are consistent, then they must go back to some ultimate Standard from which the RHs proportional calculations were drawn.

A Summary

How could the Greeks, who had a very poor number system which used letters of the alphabet without a zero, who furthermore were confused by "irrationals", as numbers which they could not calculate arithmetically ----. how could they have determined with exactitude the numbers which are discussing, and used them in architectural design?

They used the above methods, establishing a rectangle of size consonant with the work to be done, ran a string or copper wire around the points as I have described, and could thus transfer a Golden Section ratio dimension to a column, to the spacing between columns, to a metope, to a plan layout. With knowledge of the properties of the 1 : 2 rectangle, and a mechanical linear method of transfer of measurement, they were able to devote themselves to subtle elements of design. And this without having to construct a numerical interface they way we have done. Our way is easier for us, with fine calculations, CAD layout with lines of no dimension, and plotters printing out to scale. But for this we have had to provide a great deal of physical equipment, and a great deal of intellectual training and preparation for any operation we undertake.

The Greek were direct, their architecture is amazingly subtle and persuasive, and I think part of their artistry comes from their use of complex mental processes, coupled with very direct and simple ways of transferring ideas into wood and stone structures.

We often speak of the golden proportions of the Parthenon in artistic and aesthetic terms, forgetting that behind all architectural art there must be a firm foundation in ultimate numbers. As Pythagoras had clearly said:

FIRST OF ALL IS NUMBER.