編輯推薦

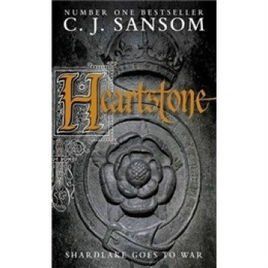

In 1545, times are perilous for London counsel Matthew Shardlake and for his country. While the English, heavily taxed and with their coinage debased by Henry VIII, prepare for a naval attack from the French at Portsmouth, Shardlake takes on a case at the request of Catherine Parr on behalf of her former servant, whose son committed suicide after discovering "monstrous wrongs" against a teenage ward he once tutored. As the 43-year-old, hunchbacked Shardlake seeks to uncover secrets in the ward's household, he also investigates the past of a presumably sane woman kept for years in Bedlam. Even with the queen's patronage, the dogged Shardlake is threatened bodily while pursuing answers to both cases, which ultimately pit him against his old court nemesis, Sir Richard Rich. The heft of this fifth in the Shardlake series may be intimidating, but Sansom's supple and action-packed prose should keep readers engaged. The novel vividly captures the Tudor scene, from its corrupt politics to the stench of its streets and the horror of battle. Historical mystery at its finest.

在1545年,倫敦的時間是危險的Shardlake律師馬太福音,為自己的國家效力。在英國,課以重稅和他們的貨幣被亨利八世的貶低,準備一個海軍攻擊的法國到朴茨茅斯的時候,Shardlake作為一種情況要求代表她凱薩琳·帕爾前的僕人,他的兒子之後自殺發掘“巨大的錯誤",對他曾經輔導一個十幾歲的病房。為43歲,Shardlake試圖揭開秘密弓腰駝背的家庭病房裡,他對以前的一個女人保持清醒多年來推測在瘋人院裡。即使有女王的人氣,頑強的Shardlake受到威脅的身體在追求回答這兩種情況下,他最終坑,對陣他的老法院強敵,理察爵士豐富。這第五個分量的Shardlake系列可以挺嚇人,但是Sansom的柔軟和火爆的散文應該使讀者訂婚了。這部小說生動地捕捉到圖多爾場景,從它的政治腐敗,發臭的街道和令人恐怖的戰鬥。在它歷史神秘倒下。

內容簡介

This is the new Shardlake mystery from the No 1 bestselling author of "REVELATION". Summer, 1545. England is at war. Henry VIII's invasion of France has gone badly wrong, and a massive French fleet is preparing to sail across the Channel. As the English fleet gathers at Portsmouth, the country raises the largest militia army it has ever seen. The King has debased the currency to pay for the war, and England is in the grip of soaring inflation and economic crisis. Meanwhile Matthew Shardlake is given an intriguing legal case by an old servant of Queen Catherine Parr. Asked to investigate claims of 'monstrous wrongs' committed against a young ward of the court, which have already involved one mysterious death, Shardlake and his assistant Barak journey to Portsmouth. Once arrived, Shardlake and Barak find themselves in a city preparing to become a war zone; and Shardlake takes the opportunity to also investigate the mysterious past of Ellen Fettipace, a young woman incarcerated in the Bedlam. The emerging mysteries around the young ward, and the events that destroyed Ellen's family nineteen years before, involve Shardlake in reunions both with an old friend and an old enemy close to the throne. Events will converge on board one of the King's great warships, primed for battle in Portsmouth harbour: the Mary Rose...

中文簡介

這是一個新的Shardlake神秘從第一暢銷作者“啟示”。夏天,1545。英國在戰爭。亨利八世的入侵法國已經嚴重錯誤的,一個巨大的法國艦隊正準備橫渡英吉利海峽。作為英國艦隊聚集到朴茨茅斯的時候,國家養軍隊來說最大的民兵從未見過。王也貶低了貨幣支付的戰爭,英國在操縱通貨膨脹和經濟危機。同時給出了馬太福音Shardlake引人入勝的案子由一個老僕人女王的凱薩琳·帕爾。要求調查聲稱的巨大的錯誤的事上得罪一個年輕的病房的法庭,哪有涉及一個神秘死亡,Shardlake巴拉和他的助手旅程朴茨茅斯。一旦到達時,Shardlake巴拉發現自己在一個城市準備成為一個戰爭地帶,Shardlake以機會也調查的艾倫Fettipace神秘的過去,一個年輕的女人被關押在這個混亂。新興的謎團圍繞年輕病房,事件破壞了艾倫的家庭十九歲之前,涉及Shardlake都在和一位老朋友團聚和一個老敵人接近的寶座上。事件將聚集在板王的一個偉大的戰艦,正確的戰鬥在朴次茅斯港口:瑪麗玫瑰…

作者簡介

C. J. Sansom was educated at Birmingham University, where he took a BA and then a Ph.D. in history. He lives in Sussex.

與受過教育之Sansom伯明罕大學,在那裡他帶疤,然後一個博士學位的歷史。他住在蘇塞克斯。

媒體評論

"engrossing."

--The Spectator (UK)

"Atmospheric anderudite. . . . Not sinceUmberto Ecopenned The Name of the Rose has a historical crime novelist captured so perfectly a people and their place, and harnessed them with such intelligence and credibility to shadowy tales of politics, misdeeds, murder and mystery."

--Lancashire Evening Post

"An enthralling historical crime novel packed with details of life in Tudor England. Highly recommended."

--Irish Independent

"Compulsively readable and highly satisfying. . . . An entirely engrossing novel with an intriguing twist."

--Daily Express

"This wonderful Tudor-era series is must reading for anydevoteeof historical mysteries."

--Margaret Cannon, The Globe and Mail

"Another fascinating story from a gifted author."

--London Free Press

"Arousingtour de force of period re-creation, testifying to Sansom's fascination with history. . . . Like all the Shardlake books, Heartstone winningly shows Sansom's crafty flair for hoodwinking even the most hawk-eyed reader. . . . What there is no doubt about . . . is the breadth of Sansom's achievement in this novel that twists together murder mystery and turbulent history."

--Peter Kemp, The Sunday Times

“引人入勝的”。

觀眾(英國)——

“大氣和知識淵博的。自從翁貝托的名字寫環保玫瑰有一個歷史小說家捕獲犯罪如此完美的子民,使自己的地方,利用他們的智力和信譽陰暗的政治故事,罪行,謀殺和神秘。”

——蘭開夏郡晚報

“一個迷人的歷史犯罪小說中擠滿了的生活細節圖多爾英格蘭。強烈推薦。”

——愛爾蘭獨立

“可讀性和高度滿意強制。一個完全引人入勝的小說和引人入勝的曲折。”

——《每日快訊

“這美妙的Tudor-era系列是必須閱讀歷史謎團的任何奉獻者。”

瑪格麗特大炮——《環球郵報》

“另一個引人入勝的故事從一個很有天賦的作家。”

——倫敦新聞自由

“休斯頓參加一個熱烈的絕技的時期賦予迫切,向Sansom與歷史的魅力。像所有的Shardlake書籍、Heartstone winningly Sansom才能顯示的狡猾,即使是最hawk-eyed讀者又是艷陽天。什麼是無庸置疑的。是Sansom的成就的寬度在這部小說中來扭曲在一起謀殺謎團和混亂的歷史。”

——彼得·坎普,《星期日泰晤士報》

精彩書摘

The churchyard was peaceful in the summer afternoon. Twigs and branches lay strewn across the gravel path, torn from the trees by the gales which had swept the country in that stormy June of 1545. In London we had escaped lightly, only a few chimneypots gone, but the winds had wreaked havoc in the north. People spoke of hailstones there as large as fists, with the shapes of faces on them. But tales become more dramatic as they spread, as any lawyer knows.

I had been in my chambers in Lincoln's Inn all morning, working through some newbriefsfor cases in the Court of Requests. They would not be heard until the autumn now; the Trinity law term had ended early by order of the King, in view of the threat of invasion.

In recent months I had found myself becoming restless with mypaperwork. With a few exceptions the same cases came up again and again in Requests: landlords wanting to turn tenant farmers off their lands to pasture sheep for the profitable wool trade, or for the same reason trying to appropriate the village commons on which the poor depended. Worthy cases, but always the same. And as I worked, my eyes kept drifting to the letter delivered by a messenger from Hampton Court. It lay on the corner of my desk, a white rectangle with a lump of red sealing wax glinting in the centre. The letter worried me, all the more for its lack of detail. Eventually, unable to keep my thoughts from wandering, I decided to go for a walk.

When I left chambers I saw a flower seller, a young woman, had got past the Lincoln's InnGatekeeper. She stood in a corner ofgatehouseCourt, in a grey dress with a dirtyapron, her face framed by a whitecoif, holding out posies to the passingbarristers. As I went by she called out that she was a widow, her husband dead in the war. I saw she had wallflowers in her basket; they reminded me I had not visited my poor housekeeper's grave for nearly a month, for wallflowers had been Joan's favourite. I asked for a bunch, and she held them out to me with a work-roughened hand. I passed her ahalfpenny; she curtsied and thanked me graciously, though her eyes were cold. I walked on, under the Great Gate and up newly pavedchanceryLane to the little church at the top.

As I walked I chided myself for my discontent, reminding myself that many of my colleagues envied my position as counsel at the Court of Requests, and that I also had the occasionallucrativecase put my way by the Queen's solicitor. But, as the many thoughtful and worried faces I passed in the street reminded me, the times were enough to make any man's mind unquiet. They said the French had gathered thirty thousand men in their Channel ports, ready to invade England in a great fleet of warships, some even with stables on board for horses. No one knew where they might land, and throughout the country men were being mustered and sent to defend the coasts. Every vessel in the King's fleet had put to sea, and large merchant ships were being impounded and made ready for war. The King had levied unprecedented taxes to pay for his invasion of France the previous year. It had been a complete failure and since last winter an English army had beenBesiegedin Boulogne. And now the war might be coming to us.

I passed into the churchyard. However much one lacks piety, the atmosphere in a graveyard encourages quiet reflection. Ikneltand laid the flowers on Joan's grave. She had run my little household near twenty years; when she first came to me she had been a widow of forty and I acallow, recently qualified barrister. A widow with no family, she had devoted her life to looking after my needs; quiet, efficient, kindly. She had caught influenza in the spring and been dead in a week. I missed her deeply, all the more because I realized how all these years I had taken her devoted care for granted. The contrast with thewretchI now had for a steward was bitter.

I stood up with aSigh, my knees cracking. Visiting the grave had quieted me, but stirred those melancholy humours to which I was naturally prey. I walked on among theheadstones, for there were others I had known who lay buried here. I paused before a fine marble stone:

Roger Elliard

Barrister of Lincoln's Inn

Beloved husband and father

1502–1543

I remembered a conversation Roger and I had had, shortly before his death two years before, and smiledsadly. We had talked of how the King had wasted the riches he had gained from the monasteries, spending them on palaces and display, doing nothing to replace the limited help the monks had given the poor. I laid a hand on the stone and said quietly, 'Ah, Roger, if you could see what he has brought us to now.' An old woman arranging flowers on a grave nearby looked round at me, an anxious frown on her wrinkled face at the sight of a hunchbacked lawyer talking to the dead. I moved away.

A little way off stood another headstone, one which, like Joan's, I had had set in that place, with but a short inscription;

Giles Wrenne

Barrister of York

1467–1541

That headstone I did not touch, nor did I address the old man who lay beneath, but I remembered how Giles had died and realized that indeed I was inviting a black mood to descend on me.

Then a sudden blaring noise startled me almost out of my wits. The old woman stood and stared around her, wide-eyed. I guessed what must be happening. I walked over to the wall separating the churchyard from Lincoln's Inn Fields and opened the wooden gate. I stepped through, and looked at the scene beyond.

Lincoln's Inn Fields was an empty, open space of heathland, where law students hunted rabbits on thegrassyhill ofconeyGarth. Normally on a Tuesday afternoon there would have been only a few people passing to and fro. Today, though, a crowd was gathered, watching as fifty young men, many in shirts and jerkins but some in the blue robes of apprentices, stood in fiveuntidyrows. Some lookedsulky, someapprehensive, some eager. Most carried the warbows that men of military age were required to own by law for the practice ofarchery, though many disobeyed the rule, preferring the bowling greens or the dice and cards that were illegal now for those without gentleman status. The warbows were two yards long, taller than their owners for the most part. Some men, though, carried smaller bows, a few of inferior elm rather than yew. Nearly all wore leather bracers on one arm, finger guards on the hand of the other. Their bows werestrungready for use.

The men were being shepherded into rows of ten by a middle-aged soldier with a square face, a short black beard and a sternly disapproving expression. He was resplendent in the uniform of the London Trained Bands, a white doublet with sleeves and upper hose slashed to reveal the red lining beneath, and a round, polished helmet.

Over two hundred yards away stood the butts, turfedearthenmounds six feet high. Here meneligiblefor service were supposed to practise every Sunday. Squinting, I made out a straw dummy, dressed in tatters of clothing, fixed there, abatteredhelmet on its head and a crude French fleur-de-lys painted on the front. I realized this was another View of Arms, that more city men were having their skills tested to select those who would be sent to the armies converging on the coast or to the King's ships. I was glad that, as a hunchback of forty-three, I wasexemptfrom military service.

A plump little man on a fine grey mare watched the menShufflinginto place. The horse, draped in City of London livery, wore a metal face plate with holes for its eyes that made its head resemble a skull. The rider wore half-armour, his arms and upper body encased in polished steel, a peacock feather in his wide black cap stirring in the breeze. I recognized Edmund Carver, one of the city's senior aldermen; I had won a case for him in court two years before. He looked uneasy in his armour, shifting awkwardly on his horse. He was a decent enough fellow, from the Mercers' Guild, whose main interest I remembered as fine dining. Beside him stood two more soldiers in Trained Bands uniform, one holding a long brass trumpet and the other ahalberd. Nearby a clerk in a black doublet stood, a portable desk with asheafof papers set on itslunground his neck.

The soldier with the halberd laid down his weapon and picked up half a dozen leather arrowbags. He ran along the front row of recruits, spilling out a line of arrows on the ground. The soldier in charge was still casting sharp, appraising eyes over the men. I guessed he was a professional officer, such as I had encountered on the King's Great Progress to York four years before. He was probably working with the Trained Bands now, a corps of volunteer soldiers set up in London a few years ago who practised soldiers' craft at week's end.

He spoke to the men, in a loud, carrying voice. 'England needs men to serve in her hour of greatest peril! The French stand ready to invade, to rain down fire and destruction on our women and children. But we remember Agincourt!' He paused dramatically: Carver shouted, 'Ay!', followed by the recruits.

The officer continued. 'We know from Agincourt that one Englishman is worth three Frenchmen, and we shall send our legendary archers to meet them! Those chosen today will get a coat, and thruppence a day!' His tone hardened. 'Now we shall see which of youLADShave been practising weekly as the law requires, and which have not. Those who have not – ' he paused for dramatic effect – 'may find themselves levied instead to be pikemen, to face the French at close quarters! So don't think a weak performance will save you from going to war.' He ran his eye over the men, who shuffled and looked uneasy. There was something ...

在教堂的墓地是和平的夏日午後。樹枝和灑在樹枝躺的石子小路,撕裂的大風從樹上的暴風雨橫掃整個國家在1545年6月。我們在倫敦輕鬆逃脫,只有少數chimneypots不見了,但風搞亂了北方。人們說的那樣大冰雹在拳頭,與形狀的面孔。但是故事變得更加戲劇性的,因為它們散布的,任何一個律師知道。

我在林肯飯店所有艙的早晨,透過一些新的內褲在法院審理的案件的要求。他們將不會聽到推遲到秋天了,結束了三位一體的法律術語王的吩咐,在早期,針對入侵的威脅。

在最近幾個月里,我已經找到了自己和我的文書工作變的不平靜。除了極少數例外同樣的情況下又上來,又在要求:要把地主從他們的土地佃農前往草場的羊羊毛貿易有利可圖,或出於同樣的原因,試圖在下議院的村莊窮人依靠的人。值得的病例,但總是一樣的。當我工作的時候,我的眼睛一直飄到這封信交一個信使從漢普頓。它躺在角落裡我的書桌,一個白色長方形,一塊紅色映封蠟的中心。這封信使我擔心,更因其缺乏細節。最後,無法保持我的思想從徘徊,我決定去散步。

當我離開的時候,我看到了一朵花賣方室,一個年輕的女人,有過去的林肯飯店守門人。她站在角落裡的門房法院,一隻灰色的裙子,一個骯髒的圍裙,她的臉白coif掩映,伸出了posies傳球的律師。她叫我去,她是一位寡婦,她的丈夫死於戰爭。我看見她在她的籃子wallflowers;他們使我想起我沒有訪問我可憐的女管家的墳墓近一個月,因為wallflowers已經瓊的最愛。我想要一大堆的問題;她抱出來work-roughened我手。我把她的一枚半便士的;她達成curtsied獻計施恩,向我道謝,但她的眼睛是冷的。我走在偉大的門,新鋪的小教堂的大法官法庭小路站在頂端。

當我走我責備自己為我的不滿,提醒自己,我的許多同事羨慕我擔任律師在法庭上請求的,我也有有利的情況下把我偶爾被女王的初級律師。但是,當很多人深思熟慮和憂心忡忡的臉在街上我通過提醒我,足以讓任何時代人的思想不安寧的。他們說,法國人在自己的渠道蒐集到三萬個港口,準備入侵英國大艦隊的戰艦,有些人甚至在船上帶有馬廄的馬。沒有人知道哪裡他們可能地,全國各地的人被招,打發來保衛他們的境界。每一船舶在王的艦隊已經叫海,大型商船被扣押和預備打仗。王前所未有的稅收徵收支付他去年入侵法國。這是一個徹底的失敗,從去年冬天的一個英國軍隊被圍困在Boulogne。和現在的戰爭可能會向我們走來。

我進了墓地。無論一個缺乏,虔誠的氣氛,鼓勵靜思墓地。我跪下來,把花在瓊的墳墓。她跑近二十年來我的家庭;當她第一次出現的時候,我的妻子,她原本是一個四十歲了,我一個初出茅廬,最近合格的律師。一個寡婦,沒有家庭,她把自己的生命去照看我的需要;安靜的、高效、和藹可親。她抓住了流感在春天的在一個星期內已經死了。我錯過了她深,所有的更多,因為我意識到這些年來我領忠實於她護理是理所當然的。將那個可憐的人相比,我現在一個管家是苦的。

我站起來可唱,嘆息一聲,我的膝蓋開裂。參觀墳墓書記安撫了我,但攪了那些我憂鬱氣質完全自然的獵物。我走在墓碑,因為有其他我所知道誰被埋在這裡。我停下來在一個精美的大理石石材:

羅傑Elliard

律師的林肯飯店

心愛的丈夫和父親

1502 - 1543

我記得羅傑和我交談過的,不久之後,達文西與世長辭的前兩年,笑得很悲傷。我們說過這些話,國王的財富已經浪費了他有了從修道院,花費在宮殿和顯示,什麼事也不做來取代和尚所幫助有限窮人。我把一隻手放在在石頭上,平靜地說:“啊,明白,如果你可以看見他把我們帶到了現在。“一個老婦人在墳墓附近插花回頭去看我,焦急的皺著她滿是皺紋的臉上看一弓腰駝背的律師說死者。我搬走了。

一個小離站在另一個墓碑,一種,像瓊的,我已將那地方,而是一個短的碑文。

賈爾斯Wrenne

紐約律師

1467 - 1541

那墓碑我沒有提及,我也沒有地址大海海底的一位老人,但我想起吉爾已經去世了,意識到我實在誘人的黑色的心情下我。

然後突然吵的噪音幾乎嚇得我不知所措。這位老婦人站在那裡,我開始在她四周,睜大眼睛。我猜要發生。我走到牆上分離從林肯飯店領域墓地,打開了木製門。我走通過,看著那場景超越。

林肯飯店領域是一個空、開放空間的heathland,那裡的法律專業學生在追捕兔子的長草的小山丘康尼賈斯。通常一個星期二的下午已經只有少數幾個人通過來回擺動。雖然,今日一群人聚集在,看著五十個年輕人,在眾多的襯衫和開衫,但有些在藍色長袍的學徒,站在五個邋遢的行。有些人看起來不高興,有些恐懼,有些充滿渴望。大多數的人把warbows軍事時代需要擁有法律實踐的歷練,儘管許多違反了規則,喜歡打保齡球蔬菜或骰子都是不合法的卡片現在對於那些沒有紳士地位。warbows兩碼的長,身體比眾民高過主人的大部分。有些人,雖然,把小弓、一些劣質的榆樹而不是紅豆杉。在幾乎所有的穿著皮革防禦護腕,另一隻手的手的手指上的保護。他們的弓已經可以使用了。

這些人被帶進一排排十由一個中年士兵方臉、短黑鬍子和一個嚴厲的否定表達。他是輝煌的統一的倫敦訓練的樂隊,一件白上衣的袖子,軟管,上了紅襯在揭示了,一個圓,擦亮的頭盔。

站在二百碼外的臀部,處理6英尺高丘瓦。這裡的人應該是符合服務練習每一個星期天。可是,我犯了一個假草,身著支離破碎的服裝,固定在那裡,一個受虐的盔,其頭部和一個簡陋的法國fleur-de-lys畫在前面。我意識到這是另一種觀點武器,多的城市人有他們的技能測試,選擇那些將被派往部隊集聚在海岸或王的船隻。我很高興,作為一個駝背的43個,我是免除服兵役。

一個豐滿的小個子男人在一個晴朗的灰馬看著那些男人洗牌到位。那匹馬,覆蓋在倫敦城外殼,穿著一件金屬面板與洞為它的眼睛,就像一個骷髏頭。騎手穿著half-armour、手臂和上身在離家不遠的拋光的鋼,一條孔雀羽毛在他寬大的黑色帽子攪拌在微風裡。我認出埃德蒙·雕工、市內的一個高級aldermen;我贏得了一次對他來說兩年前在法庭上。他看上去很不安,在他的盔甲,笨拙地在他的馬。轉移他是一個像樣的足夠的人,從Mercers行會,其主要興趣我記得美食。在他身旁的兩個人站立在受訓帶更多的士兵制服,舉行一個長的黃銅喇叭,另一個是長戟。附近的店員黑色上衣站,攜帶型的桌子上面捆報紙拋出的套在他的脖子上。

士兵們用長戟放下他的武器,拿起了半打皮革arrowbags。他跑著前排的戰士,溢出一個箭頭線在地上。士兵們還鑄造負責鋒利,看一下這些人。評價我猜想他是位職業軍官,如我所遇到的最偉大的進步,紐約王的四年之前。他可能是訓練有素的樂隊一起工作了,一個軍的志願士兵在倫敦設定幾年前實行的士兵的工藝在星期的結束。

他對這兩個人,一聲,攜帶的聲音。英國人的需要服務於她最大的危險的時刻!法國人準備入侵,象雨降火、破壞我們的婦女和兒童。但我們記得,也!”他停了戲劇性的:卡說:“喔!',其次是新兵。

軍官繼續說道。“我們知道從一個英國人,也值得三個法國人,我們將給我們的傳奇射手迎接他們!那些被選今天將得到一件外套,thruppence一天了!“他的語氣硬化。“現在,我們將會看到你們哪一個小伙子已經練了每周按法律要求,沒有。那些沒有-他停頓了戲劇性的效果-可能會發現自己被徵收而得過長槍兵,面對法國親密接觸!所以不要認為一個脆弱的表現必救你們脫離要去參戰。“他跑他的眼睛的人,看起來很不自在。慢吞吞地有一些…