計算機雛形

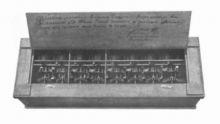

Pascaline(加法器)

滾輪式加法器

滾輪式加法器1642年,法國哲學家兼數學家布累斯·巴斯柯(Blaise Pascal)發明了第一台真正的機械計算器——加法器(Pascaline)。

全名為滾輪式加法器,當初發明它的目的是為了幫助父親解決稅務上的計算。其外觀上有6個輪子,分別代表著個、十、百、千、萬、十萬等。只需要順時針撥動輪子,就可以進行加法,而逆時針則進行減法。原理和手錶很像,算是計算機的開山鼻祖了。

帕斯卡

帕斯卡1623年出生在法國一位數學家家庭,他三歲喪母,由擔任著稅務官的父親拉扯他長大成人。從小,他就顯示出對科學研究濃厚的興趣。

少年帕斯卡對他的父親一往情深,他每天都看著年邁的父親費力地計算稅率稅款,很想幫助做點事,可又怕父親不放心。於是,未來的科學家想到了為父親製做一台可以計算稅款的機器。19歲那年,他發明了人類有史以來第一台機械計算機。

滾輪式加法器(1623-62)

滾輪式加法器(1623-62)帕斯卡的計算機是一種系列齒輪組成的裝置,外形像一個長方盒子,用兒童玩具那種鑰匙旋緊發條後才能轉動,只能夠做加法和減法。然而,即使只做加法,也有個“逢十進一”的進位問題。聰明的帕斯卡採用了一種小爪子式的棘輪裝置。當定位齒輪朝9轉動時,棘爪便逐漸升高;一旦齒輪轉到0,棘爪就“咔嚓”一聲跌落下來,推動十位數的齒輪前進一檔。

帕斯卡發明成功後,一連製作了50台這種被人稱為“帕斯卡加法器”的計算機,至少現在還有5台保存著。比如,在法國巴黎工藝學校、英國倫敦科學博物館都可以看到帕斯卡計算機原型。據說在中國的故宮博物院,也保存著兩台銅製的複製品,是當年外國人送給慈僖太后的禮品,“老佛爺”哪裡懂得它的奧妙,只把它當成了西方的洋玩具,藏在深宮裡面。

滾輪式加法器

滾輪式加法器帕斯卡是真正的天才,他在諸多領域內都有建樹。後人在介紹他時,說他是數學家、物理學家、哲學家、流體動力學家和機率論的創始人。凡是學過物理的人都知道一個關於液體壓強性質的“帕斯卡定律”,這個定律就是他的偉大發現並以他的名字命名的。他甚至還是文學家,其文筆優美的散文在法國極負盛名。可惜,長期從事艱苦的研究損害了他的健康,1662年英年早逝,死時年僅39歲。他留給了世人一句至理名言:“人好比是脆弱的蘆葦,但是他又是有思想的蘆葦。”

詳解

A Pascaline, signed by Pascal in 1652

A Pascaline, signed by Pascal in 16521645年,布萊士·帕斯卡發明了名為alternatively the Pascalinaor the Arithmetique的當時世界上的第二台機械計算機。第一台是1623年發明的Wilhelm Schickard。

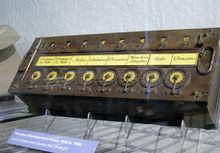

Pascaline made for French currency.

Pascaline made for French currency.Pascal began towork on his calculator in 1642, when he was only 19 years old. He had beenassisting his father, who worked as a tax commissioner, and sought to produce adevice which could reduce some of his workload. Pascal received a RoyalPrivilege in 1649 that granted him exclusive rights to make and sellcalculating machines in France.& nbsp; By 1652 Pascal claimed to have produced some fifty prototypes and sold justover a dozen machines, but the cost and complexity of the Pascaline—combined with the fact that it could only add and subtract, and the latter with difficulty—was a barrier to further sales, and production ceased in that year. By that time Pascal had moved on to other pursuits, initially the study ofatmospheric pressure, and later philosophy.

Pascalines camein both decimal and non-decimal varieties, both of which exist in museumstoday. The contemporary French currency system was similar to the Imperialpounds ("livres"), shillings ("sols") and pence("deniers") in use in Britainuntil the 1970s.

In 1799 France changedto a metric system, by which time Pascal's basic design had inspired other craftsmen,although with a similar lack of commercial success. Child prodigy GottfriedWilhelm Leibniz devised a competing design, the Stepped Reckoner, in 1672 whichcould perform addition, subtraction, multiplication and division; Leibnizstruggled for forty years to perfect his design and produce sufficientlyreliable machines. Calculating machines did not become commercially viableuntil the early 19th century, when Charles Xavier Thomas de Colmar'sArithmometer, itself using the key break through of Leibniz's design, wascommercially successful.

開蓋概覽

開蓋概覽The initialprototype of the Pascaline had only a few dials, whilst later productionvariants had eight dials, the latter being able to deal with numbers up to9,999,999.

The calculatorhad spoked metal wheel dials, with the digit 0 through 9 displayed around thecircumference of each wheel. To input a digit, the user placed a stylus in thecorresponding space between the spokes, and turned the dial until a metal stopat the bottom was reached, similar to the way a rotary telephone dial is used.This would display the number in the boxes at the top of the calculator. Then,one would simply redial the second number to be added, causing the sum of bothnumbers to appear in boxes at the top. Since the gears of the calculator onlyrotated in one direction, negative numbers could not be directly summed. Tosubtract one number from another, the method of nines' complements was used. Tohelp the user, when a number was entered its nines' complement appeared in abox above the box containing the original value entered.

滾輪式加法器

滾輪式加法器